-

Neither agree nor disagree I'm submitting an answer even though I'm agnostic and not expert on this. One issue is that isolating "inflation" from the associated context, and treating inflation as a cause of other outcomes, is a normative choice already both in suggesting a mental model and in focus. Despite my economics training, I have to say that I do not understand why we try to tune consumer prices through modulating asset prices, continue to operate a somewhat-17th-Century monetary system, nor why despite insistence on defining inflation as a "monetary phenomenon", public reports of inflation rarely distinguish between supply shock causes, steady increases in the fraction of GDP that is public goods (which therefore causes an increase in the general price of things, due to taxes), and actual "monetary" or expectations effects. The intense public focus on inflation, as on GDP, probably does more to skew people's conception of what is important in life than it does to usefully steer expectations. The evidence from wellbeing (SWL) showing the relative importance of unemployment versus inflation is more than two decades old, and it seems still not properly considered by policy makers. Also like GDP, these narrow index numbers hide the distribution. Rapid price changes (for instance, in energy, or in general prices) are opportunities to help and to redistribute, in addition to stabilizing the economy. In any case, back to the broader context: the supply (staple grains, etc) shocks and conflict and polarization due to social media algorithms and environmental challenges all loom large, and the threat of inflation on wellbeing cannot be seen outside of the context of the other simultaneous threats.

Professor Chris Barrington-Leigh

Professor, McGill University -

Agree As long as wage increases lag inflation household budgets will be under pressure. With labour shortages in many countries, as people run out of savings it may bring more people marginally attached to the labour force back into job, which in itself could increase demand for goods and services due to more money in people's pockets. The unknown factor here is how much of this inflationary pressure is driven by the supply side issues from countries like China who are still (COVID) locked down and their factories either not operating or operating at reduced production levels (there is visual evidence of the absence of Chinese imports on supermarket shelves. There are upwards of 12 month delays in new motor vehicle (e.g. Toyota) deliveries arising from Taiwan/Chinese factories inability to provide electronic components; car prices are rising. Same goes for general electrical goods e.g. flat screen TVs etc .....

Doctor Tony Beatton

Visiting Fellow, Queensland University of Technology (QUT) -

Completely agree Inflation reduces purchasing power of wages and incomes even though it reduces the real value of debt for debtholders. The first effect dominates

Professor Leonardo Bechetti

Professor of Economics, University of Rome Tor Vergata -

Agree The current inflation rate exceeds the rate of wage growth for most people, thus reducing real purchasing power. Inflation in general creates uncertainty and anxiety. Moreover, the central banks' responses will likely lead to unemployment and other negative economic effects, reducing future well-being.

Professor Daniel Benjamin

Associate Professor of Economics, University of Southern California -

Agree Rising prices mean less purchasing power and will -as we can see in the present case- impact quite strongly on all households for instance with regard to energy and food prices. This hurts poorer households economically and hence will translate into lowered wellbeing overall. In addition, inflation might negatively impact on wellbeing on top of the above mechanism through increased economic uncertainty and the anxieties it may raise.

Professor Martin Binder

Professor of Socio-Economics at Bundeswehr University Munich -

Agree Inflation will negatively impact families economic situation (especially the poorest, who consum a larger proprtion of their income on basic goods, and often has debts or don't have savings). The econoomic recession that will come hand by hand will increase uncertainty and reduce occupation, which will decrease wellbeing further

Professor Ada Ferrer-i-Carbonell

Professor of Economics, IAE-CSIC -

Agree High inflation (which will be accompanied by prices of different things, including wages, rising at different and unpredictable rates) inevitably means higher uncertainty about the adequacy of household budgets to cover the standard of living to which one and one's family is accustomed, and this translates to more everyday financial insecurity, which will depress wellbeing.

Professor Gigi Foster

Professor, School of Economics, UNSW School of Economics -

Completely agree This is the clear result of many serious empirical studies

Professor Bruno Frey

Visiting Professor of Economics and Wellbeing, University of Basel -

Completely agree This is a no-brainer. High levels of inflation destroy savings and should be understood as a raid by the money-authorities on the holdings of the population, called a seinorage tax. That leads to distortions in the economy, uncertainty, evasive behaviour, and widespread misery. Because this time the price rises are in crucial commodities like food and fuel, the poor will be particularly hard hit and we can expect widespread famines and riots in poor countries. We are currently wittnessing a genuine wellbeing disaster.

Professor Paul Frijters

Professorial Research Fellow, CEP Wellbeing Programme, London School of Economics -

Completely agree "We know from the classic paper by Di Tella et al (2001) that inflation impacts negatively on people's life satisfaction. What makes the current bout of inflation particularly serious in this regard is that it was unanticipated by the vast majority of people; hence they did not prepare themselves for it (e.g. by investing in inflation-adjusted bonds). Wages have also inevitably lagged behind price increases so real wages for most people have fallen. Asset prices -which rose strongly prior to the current rise in the price of goods and services - are now falling so people's investments are worth less in nominal terms, not just in real terms. The majority of people will therefore be affected negatively by this unanticipated, and severe, rise in inflation. Reference: Di Tella, Rafael, Robert MacCulloch and Andrew J. Oswald. 2001. ""Preferences over Inflation and Unemployment: Evidence from Surveys of Happiness."" American Economic Review, 91(1), 335-341. "

Professor Arthur Grimes

Chair of Wellbeing and Public Policy, School of Government, Victoria University of Wellington -

Agree Judging by the fact that governments in power appear to get punished for high inflation, at least subjectively this may be the case. But inflation also creates winners (e.g. those who have borrowed money) and it also depends on what happens to earnings

Professor Arie Kapteyn

Professor of Economics, University of Southern California -

Completely agree The current rise in inflation is mostly driven by supply-side factors (energy cost, disrupted supply chains). Contrary to demand-driven inflation, which generally increases prices and incomes in lockstep, this kind of inflation really makes people poorer and reduces their well-being. Moreover, the dramatic discrepancy between political inflation targets and actual inflation rates increases uncertainty about the future development of prices and living standards. Such uncertainty is also detrimental to well-being.

Professor Andreas Knabe

Professor (Chair in Public Economics), Otto-von-Guericke-University Magdeburg -

Completely agree The recent rise of inflation will harm the majority of people because it takes place in a much more deteriorated social situation than in the previous inflationary wave. The US economy had recovered well, but corporate and consumer sentiments are generally negative. The problem of inflation appears to be the catalyst for social discontent. It increases the uncertainty that was already high because of the pandemic, the war in Ukraine, mass shootings, and political divides. In Europe, the situation changes only because inflation is lower, but unemployment is higher.

Professor Maurizio Pugno

Full Professor of Economics, University of Cassino -

Completely agree In the short run, the increase of average prices will affect people's purchasing power. In so far as the increase will affect basic goods, poor people will likely suffer much more and much earlier than richer people. In the long run, the impact of inflation on well-being will depend on the specific policies adopted to contain inflation. For instance, increasing interest rates will likely reduce investments and plausibly give raise to unemployment, which is definitely bad for well-being.

Doctor Francesco Sarracino

Economist, Research Division of the Statistical Office of Luxembourg -STATEC -

Completely agree Inflation erodes real incomes, generates uncertainty, damages provision for the future and causes conflict. All of these will damage wellbeing and promote unhappiness and misery for the majority.

Professor Daniel Sgroi

Professor of Economics, University of Warwick -

Agree "The increase in prices in a timely manner from one moment to another is not inflation. Inflation is the sustained increase in this increase, for prolonged periods. Therefore, inflation is a phenomenon that has a strong impact on the well-being (physical, mental, etc.) of most people in the affected countries. For example, let us think of the poorest and suppose that 100% of their budget is going to be spent (given that they have neither the capacity to save nor to cover themselves in a bank that readjusts them). An inflation of 20% increases the price that these people must pay for final goods by 20%. Since in most cases, the poorest do not receive adjustments for inflation, their budget is also reduced by 20%, which affects both their physical and mental well-being and makes them poorer and poorer. The same happens with middle class people who cannot cover themselves from these inflationary rises. I make this clarification, since in certain countries, some scarce salaries from work do contemplate (voluntarily) adjustments for inflation. Ignoring certain more specific factors-effects, on average, these people could “theoretically†cover the costs of inflation. The same happens with people with higher incomes, those who can seek the form of protection they require. However, in developing countries I tend to think that they are the least. Another important case to differentiate, are the financial companies. For example, with high inflation, the demand for credit increases, raising interest rates, which benefits lenders. "

Professor Wenceslao Unanue

Associate Professor, Business School, Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez -

Agree A negative effect of inflation on average happiness in nations has been shown in the past and is likely to exist today

Professor Ruut Veenhoven

Professor of Sociology, Erasmus University Rotterdam -

Completely agree "Starting with Di Tella et al. (2001), a considerable literature has established that subjective wellbeing is negatively related to inflation. In a study covering 30 OECD countries in America, Asia and Europe, the effect was found to be strongly regressive, that is, the strength of the relationship is deccreasing in household income, being only half as strong (and only marginally significant) in the top quartile of the income distribution than in the bottom quartile (Welsch and Kühling 2015). Inflation thus impacts negatively on the wellbeing of the majority of people, but particularly on that of the poor. Di Tella, R., MacCulloch, R.J., Oswald, A.J. (2001), Preferences over Inflation and Unemployment, American Economic Review 91, 335-341. Welsch, H., Kühling, J. (2015), Macroeconomic Preferences by Income and Education Level,: Evidence from Subjective Well-Being Data, Review of Economics and Finance 5, 15-32 . "

Professor Heinz Welsch

Professor of Economics, University of Oldenburg -

Agree I agree with this statement -- rising price inflation increases the cost of living of most people thus reducing their material well-being. However, the magnitude of this effect on overall well-being may still be small and temporary. This will depend on the extent to which wages respond -- for workers what matters is real wages -- and the extent to which other forms of income are indexed to inflation. In Australia for example pensions and out-of-work benefits are adjusted to maintain their value against increases in the cost of living. Rapidly rising inflation (so long as it does not morph into hyper-inflation) is thus a temporary problem. Indeed, the bigger consequences for well-being may come via the impacts of government responses to rein in inflation: Increased interest rates and reduced fiscal spending, for example, will typically slow economic growth and reduce employment levels, and generally research has found that employment matters more to subjective wellbeing than income.

Professor Mark Wooden

Professorial Research Fellow and Director of the HILDA Survey Project, Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic and Social Research, Faculty of Business and Economics, University of Melbourne -

Agree When wages fail to keep pace with rapidly increasing prices, purchasing power of consumers is eroded. However, in addition to this effect on households and their ability to afford goods and services, there is also the psychological cost imposed on individuals, which often surpasses the actual burden in terms of standards of living.

Professor Stephen Wu

Professor of Economics, Hamilton College

The rise in global inflation will impact negatively on the wellbeing of the majority of the people in affected countries.

Policy responses to combat the rise in global inflation will impact negatively on the wellbeing of the majority of the people in affected countries.

-

Agree "This seems to be received wisdom. Rising interest rates to combat inflation always comes with apologies about the ""needed pain"", so it is well recognized that it is going to hurt people. The wellbeing science helps us by pointing out that we should tolerate a bit more inflation if we can avoid more unemployment. To benefit properly from this insight, we need to move far beyond the absurd blunt tools we have now. There are other, fiscal, ways to accomplish the same thing in principle, for instance by modulating the availability of an employer of last resort, or by modulating short-term taxes: governments have been willing to hand out trillions during the pandemic, but taxing it back, acutely, to bring prices down more directly than through interest rates is for some (political!) reason off the table. Governments are currently planning central bank digital currencies, which opens enormous opportunities for a re-write of a bunch of macro-economics, or at least policy, but due to the influence of entrenched interests, I think many are angling to change as little as possible about our leveraged banking system. "

Professor Chris Barrington-Leigh

Professor, McGill University -

Agree I expect they will. I cannot see how a single country's policy change(s) can correct this global malaise. Plus there is the issue of inflation being driven by the oil and gas shortages arising from the Ukraine war. Deja vu late 1970s early 1980s driven by the OPEC oil crisis all over again, then we went into deep recession for a number of years, real estate values plummeted. not goood!

Doctor Tony Beatton

Visiting Fellow, Queensland University of Technology (QUT) -

Disagree Interest rate rises will make borrowing more expensive thereby reducing wellbeing. Antinflationary policies consisting of subsidies helping the poor to afford the reduction in purchasing power or to pay energy bills will however improve their wellbeing

Professor Leonardo Bechetti

Professor of Economics, University of Rome Tor Vergata -

Agree See previous. However, the policy responses are likely better than the alternative of letting inflation get out of control. That would require an even bigger policy response in the future, leading to greater economic misery.

Professor Daniel Benjamin

Associate Professor of Economics, University of Southern California -

Neither agree nor disagree I think any shortrun harm of such policies will be outweighed by the long run positive effects of not having (high) inflation.

Professor Martin Binder

Professor of Socio-Economics at Bundeswehr University Munich -

Agree The monetary policy to contain inflation will necessarily lead to a reduction in wellbeing. Depending on the government size and capacity, fiscal policy will compensate the poorest. It is time for governments to protect the weaker and to invest on productivity

Professor Ada Ferrer-i-Carbonell

Professor of Economics, IAE-CSIC -

Neither agree nor disagree It depends both which policies are being pursued, and what timeline you are looking at. In the short run, printing more stimulus money or giving people subsidies for certain purchases in an attempt to reduce the negative impact of inflation on household budgets may not reduce wellbeing in the short run. However, in the longer run, more government spending is likely to create further economic problems (including even more inflation) that will further depress wellbeing. Governments may also try to control inflation directly using monetary policy, which may have negative wellbeing effects (for example due to increased financial insecurity resulting from a rise in mortgage repayments) in the short run.

Professor Gigi Foster

Professor, School of Economics, UNSW School of Economics -

Completely agree The negative income effects produced by the government intervention affects happiness negatively

Professor Bruno Frey

Visiting Professor of Economics and Wellbeing, University of Basel -

Neither agree nor disagree The main short-run option to combat inflation is an increase in interest rates, which negatively affects people with mortgages and high cheap loans, so the indebted. That will cause misery as well, but the alternative (let inflation become hyperinflation) is probably worse, so its about the likely balance of effects. The major cause was money printing during lockdowns and the supply disruptions of lockdowns, which should be avoided in the future. We are 'merely' seeing the inevitable consequence of those actions by authorities over the last 40 months. In the longer run authorities can and should (from a wellbeing point of view) improve many aspects of the monetary and regulatory system.

Professor Paul Frijters

Professorial Research Fellow, CEP Wellbeing Programme, London School of Economics -

Agree "Interest rates are rising around the world in response to the burst in inflation. Interest rate rises will hurt some people - especially those holding bonds or having to refinance mortgages etc. Some firms will become insolvent and so some jobs will be lost. Other people - especially older savers who have the bulk of their savings in short-term debt securities - will benefit from the rise in interest rates (noting, nonetheless, that real interest rates remain negative almost everywhere). As usual, therefore, a monetary tightening will have distributional effects with some people's wellbeing improving (e.g. for older savers) and some people's wellbeing deteriorating; the latter group is likely to be larger. Fiscal contractions will also tend to impact negatively on certain groups. Having let the inflation cat out of the bag to bring about previous short term gains, we now will bear the longer term costs of containing it. "

Professor Arthur Grimes

Chair of Wellbeing and Public Policy, School of Government, Victoria University of Wellington -

Disagree if inflation is bad then combatting it by itself cannot be bad. But there may be some short term pain

Professor Arie Kapteyn

Professor of Economics, University of Southern California -

Agree The standard response to inflation is monetary contraction. This will decrease aggregate demand and ease inflationary pressures. The downside of this policy response is that is that it also reduces employment. So real incomes fall in either case, if not through higher prices, then through less employment. The latter option, however, is probably even worse for well-being, since unemployment hurts more than what can be attributed to the associated income loss.

Professor Andreas Knabe

Professor (Chair in Public Economics), Otto-von-Guericke-University Magdeburg -

Agree A restrictive monetary policy to combat inflation obviously worsens people's well-being because the consequent unemployment is perceived as an even worse evil. This effect could be mitigated by a fiscal and subsidy policy that had already been used to alleviate the economic effects of the pandemic, and that should now offset the redistributive effects of inflation.

Professor Maurizio Pugno

Full Professor of Economics, University of Cassino -

Agree In the short run the countermeasures to inflation will likely negatively affect well-being via reduced investments. The increase in the price of energy and of some goods may re-orient consumption towards alternative and perhaps more sustainable resources to the benefit of people and of the environment. The adjustment, however, will require some time during which people's well-being will decline.

Doctor Francesco Sarracino

Economist, Research Division of the Statistical Office of Luxembourg -STATEC -

Neither agree nor disagree It is hard to know whether policy responses will negatively affect the majority as there is no standard global response and there remains significant disagreement within and between governments on the underlying causes of the problem, how best to tackle those causes or mitigate the effects.

Professor Daniel Sgroi

Professor of Economics, University of Warwick -

Agree The Central Bank of Chile has the following statement on its main page: “Our mission is to keep inflation under control and contribute to the stability of the financial system, thus playing a part in the country’s development and the progress of its inhabitants.†Therefore, it is clear that one of its policies, required by law as in some other countries in the world, is to control inflation. His goal was to keep inflation around 3% a year, so he must. Today, it borders on 10-12%, so you need to act urgently, but smartly. For example, Central Banks tend to raise interest rates in order to decrease demand when the country is “overheatedâ€. But this policy is not harmless. Raising interest rates leads to higher interest rates on bank loans, leading people to decrease their demand for property (and other goods) and to increase monthly payments for properties already purchased if the loans are indexed to inflation as is my case in Chile). All this could reduce the purchasing power of households, lowering domestic demand, and therefore, reducing economic growth. These sheer effects could have consequences for the present and future well-being of those most affected by certainty and uncertainty (again, I think, the poorest). However, as in the previous case, there are companies that could theoretically win. Those companies that see the value of their goods increased, but the cost can be controlled or may have lower increases than the sale value of final goods.

Professor Wenceslao Unanue

Associate Professor, Business School, Universidad Adolfo Ibáñez -

Neither agree nor disagree Not sure whether the medicine will be worse than the disease. The balance of effect is likely to vary across nations and publics and the present state of knowledge does not allow a prediction of how anti-inflation policies will pann out for whom

Professor Ruut Veenhoven

Professor of Sociology, Erasmus University Rotterdam -

Agree It is to be expected that fighting inflation by monetary policy will come at a cost in terms of a recession, particularly in Europe. As also established in the pertinent literature, recessions and the rise in unemployment accompanying them also have strong negative impacts on wellbeing. Policy responses to inflation should therefore be targetted towards relieving the poorer segments of the population from the impacts of inflation through fiscal measures rather than by fighting inflation at all cost.

Professor Heinz Welsch

Professor of Economics, University of Oldenburg -

Disagree "There is no simple answer to this question. As stated in my answer to the previous question, policy responses to rein in inflation are typically focussed on the demand side, and reductions in demand will mean reduced employment levels and heightened job insecurity, adversely affecting the well-being of some (but especially the inexperienced and those without skills in demand). So, this suggests the answer is yes -- government responses do typically reduce population well-being. Nevertheless, the counterfactual -- letting inflation run its course -- is likely far worse. If prices are continually increasing faster than nominal incomes, material well-being is reduced for all. More importantly, there is the risk of price-wage spirals. Higher prices encourage higher wage outcomes, which cause firms to either raise prices further or reduce costs by reducing employment. Investment decisions are also adversely affected, both because the real return on investment falls and because of the greater levels of general economic uncertainty. And reduce investment again means fewer jobs. So in short, the counterfactual, where there is no stabilizing policy reaction from Governments (and central banks) will likely mean far more adverse consequences for population well-being. "

Professor Mark Wooden

Professorial Research Fellow and Director of the HILDA Survey Project, Melbourne Institute: Applied Economic and Social Research, Faculty of Business and Economics, University of Melbourne -

Neither agree nor disagree I think this depends on the nature of the responses, and it also depends on a country's particular situation.

Professor Stephen Wu

Professor of Economics, Hamilton College

INFLATION AND WELLBEING

World Wellbeing Panel Survey | July 2022

by Tony Beatton (Queensland University of Technology), Ada Ferrer-i-Carbonell (IAE-CSIC and BSE), Paul Frijters (LSE)Arthur Grimes (Victoria University of Wellington)

There was an almost full agreement with statement 1, 19 of our panelists agreed or completely agreed with the statement, while only one opted for “neither agree nor disagree”. This question has generated more consensus among our panelists than we typically see.

Some of our panelists’ (Bruno Frey, Ruut Veenhoven, Heinz Welsch, and Arthur Grimes) refer to the empirical evidence that shows a strong and consistent negative correlation between happiness or life satisfaction and inflation (Di Tella et al., 2001) and to the fact that the correlation is stronger for those at the bottom of the income distribution (Welsch and Kühling, 2015). Arie Kapteyn argued that observed individual behaviour indicates that inflation is wellbeing damaging, as “governments in power appear to get punished for high inflation”.

Other panelists, who agreed with the statement, focussed on the different channels through which inflation can affect wellbeing and pointed to the different impact across social groups. The most mentioned channel is the (probable) decrease in real wages and income associated with higher inflation that will lead to a wellbeing loss (Arthur Grimes, Leonardo Becchetti, Ada Ferrer-i-Carbonell, Arie Kapteyn, Daniel Benjamin, Stephen Wu, Wenceslao Unanue, Martin Binder, and Francesco Sarracino). Mark Wooden argued that this can be temporary, as wages might respond to inflation. He notices, for example, that in Australia “pensions and out-of-work benefits are adjusted to maintain their value against increases in the cost of living”. In this line, Wenceslao Unanue states that the inflation will impact more on the poorest who in many cases do not receive income adjustments for inflation. Francesco Sarracino argues that the price increases will affect the poor most, because inflation increases the price of what we need to feed our families.

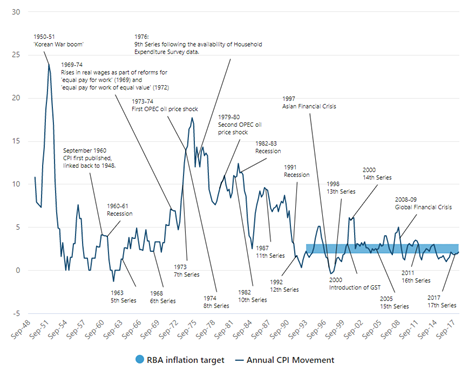

Andreas Knabe emphasizes the fact that inflation driven by supply-side factors, such as the current one clearly makes people poorer and reduces their well-being. Tony Beatton wonders “[…] how much of this inflationary pressure was initiated by Government COVID policy responses and resultant supply side issues in countries like China, who are still (COVID) locked down […]”. He continues by reminding us that in 1973-74 we saw runaway inflation ignited by the first OPEC oil shock (Figure 1); today we see oil and gas supply issues with Russia again fuelling inflationary pressures.

Figure 1: Australian inflation rate 1948-2017 (What is inflation? Why is the CPI so high? And how is the RBA planning to bring it back down? – ABC News)

Another repeatedly mentioned channel, beside real incomes, is the correlation between inflation and financial uncertainty and insecurity and subsequent anxiety (Daniel Sgroi, Daniel Benjamin, Gigi Foster, Andreas Knab, Martin Binder). Stephen Wu relates to this and talks about the psychological cost that can go beyond actual costs in terms of standard of living. Andreas Knabe writes “[…] the dramatic discrepancy between political inflation targets and actual inflation rates increases uncertainty about the future development of prices and living standards. Such uncertainty is also detrimental to well-being.” Maurizio Pugno highlights that this uncertainty comes on top of an already very deteriorated situation and cites in example the COVID pandemic or the war in Ukraine.

The panelists also emphasized that some individuals might win from inflation, notably debt holders (Leonardo Becchetti, Arie Kapteyn, and Wenceslao Unanue), although Arthur Grimes contested this by arguing that asset prices are falling “so people's investments are worth less in nominal terms, not just in real terms”.

Maurizio Pugno and Paul Frijters are perhaps the ones that show more worries about the current situation. Paul Frijters argues that inflation harms savings and leads to distortions, uncertainty, evasive behaviour, and widespread misery. Like other panelists who agreed with the statement, Paul emphasizes that inflation is particularly harmful to the poor, because price increases occur on their everyday commodities, notably food and energy. Paul finishes his statement by writing “[…] we can expect widespread famine and riots in poor countries. We are currently witnessing a genuine wellbeing disaster.”

Chris Barrington-Leigh also cites earlier evidence showing “the relative importance of unemployment versus inflation […]” and expects “[…] conflict and polarization due to social media algorithms and environmental challenges all loom large, and the threat of inflation on wellbeing cannot be seen outside of the context of the other simultaneous threats.”

There was less agreement in relation to Statement 2, 11 agreed or completely agreed with the statement, 6 neither agree nor disagree, and 3 disagreed with the statement.

Those who agree with this statement focused on the impact of different policies aimed at containing inflation (Bruno Frey, Tony Beatton, and Chris Barrington-Leigh). First, interest rates are rising as a response to inflation (monetary policy) which will deteriorate the economic situation of those families who have debt such as home mortgages (Arthur Grimes). This monetary policy will probably lead to an economic recession with firm closures, demand reduction, and unemployment increase (Arthur Grimes, Heinz Welsch, Maurizio Pugno, and Wenceslao Unanue). Unemployment increase will lead to considerable wellbeing losses (Andreas Knabe, Arthur Grimes, Heinz Welsch, Maurizio Pugno, and Chris Barrington-Leigh). Our panelists argued that Government policy responses and their consequences will have redistributive consequences from the income-reliant poor to the capital-holding rich, thus harming the poorest and the most vulnerable.

Secondly, some panelists argued about the importance of governments not entering into contractionary fiscal policy, but instead developing policies aimed at alleviating poverty and compensating or the distributive effects of inflation (Ada Ferrer-i-Carbonell, Heinz Welsch and Maurizio Pugno) as well as other expansive fiscal policies (Chris Barrington-Leigh). If this is not done, we can expect further deterioration in wellbeing (Arthur Grimes).

The fiscal and monetary contraction (e.g., through increased unemployment) will harm wellbeing more than inflation and real income loss (Andreas Knabe) and will disproportionally impact upon the poorest and the more vulnerable (Arthur Grimes). Nevertheless, some panelists argue that not responding to inflation might lead to worse economic misery in the future (Daniel Benjamin, Martin Binder, and Mark Wooden). Paul Frijters, who neither agrees or disagrees with the statement, writes that “[…] it is about the likely balance of effects” and he continues: “The major cause was money printing during lockdowns and the supply disruptions of lockdowns, which should be avoided in the future. We are 'merely' seeing the inevitable consequence of those actions by authorities over the last 40 months. In the longer run authorities can and should (from a wellbeing point of view) improve many aspects of the monetary and regulatory system.”

In Australia, this process began last week with the initiation of a review of the Reserve Bank of Australia which earlier this year, when rates were close to zero, predicted no interest rate rises until 2023 and has just this month suggested a ‘balanced rate’ should be closer to 3 - 3 1/2 percent. Tony Beatton suggests this may be the politicians shining the light of investigation away from revealing the consequences of the Government’s COVID policies.

On the bright side, some panelists think the energy price increase might change consumption patterns towards more sustainable goods and energy sources (Francesco Sarracino).

Those who neither agree or disagree with statement 2 argued that it will depend on how each country implements its inflation-response policies and whether they look at the short or long term (Ruut Veenhoven, Daniel Sgroi, Gigi Foster, Stephen Wu, and Martin Binder).

Finally, a set of panelists disagreed with statement 2. Arie Kapteyn argued that “if inflation is bad then combatting it by itself cannot be bad. But there may be some short-term pain” and Leonardo Becchetti balanced the statement by arguing that while monetary policy to fight inflation will be wellbeing damaging, this might be accompanied by expansive fiscal policy, which will improve wellbeing. Mark Wooden and a number of other panelists conclude by stating: not fighting inflation will be worse than the policies required to contain it.

References

Di Tella, Rafael, Robert MacCulloch and Andrew J. Oswald. 2001. "Preferences over Inflation and Unemployment: Evidence from Surveys of Happiness." American Economic Review, 91(1), 335-341.

Welsch, H., Kühling, J. (2015), Macroeconomic Preferences by Income and Education Level,: Evidence from Subjective Well-Being Data, Review of Economics and Finance 5, 15-32 .